Perspective: Does the First Amendment Protect a Right to Protest at Supreme Court Justices’ Homes?

A leaked draft opinion by Justice Samuel Alito in Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization that looks like it will overturn the Supreme Court’s 1973 Roe v. Wade decision has led to many protests and rallies.

New fencing limits the access of protesters to the Supreme Court building and plaza. These limits probably don’t violate the First Amendment rights to assembly and petition.

Protests aren’t just occurring at the justices’ place of business but at some of their homes as well.

Can an officer arrest someone for simply protesting on a public sidewalk or street outside a justice’s house? The short answer is yes — unless it is a mobile, nonthreatening protest that does not attempt to influence the judge’s ruling in a pending case.

How likely are arrests? The Senate has unanimously approved a bill authorizing police protection for the nine justices and their families if deemed necessary, and President Joe Biden signed it into law.

The justices live in Virginia, Maryland or the District of Columbia, each of which has a law addressing “residential picketing.”

- Virginia prohibits “picketing before or about the residence or dwelling place of any individual, or [assembling] with another person or persons in a manner which disrupts or threatens to disrupt any individual’s right to tranquility in his home.”

- Maryland says “a person may not intentionally assemble with another in a manner that disrupts a person’s right to tranquility in the person’s home.”

- The District of Columbia is the most specific, saying a group of three or more people may not “target a residence for purposes of a demonstration” between the hours of 10 p.m. and 7 a.m., while wearing a mask, or without having notified the police department about the place and time of the demonstration.

Given its specificity, it is not surprising that the district law is the least likely to violate the First Amendment. That’s because, while there is a general right to protest on a public sidewalk, the Supreme Court has identified certain acceptable restrictions on that right.

In 1988 in Frisby v. Schultz, the court said that a law banning all picketing of any kind that is targeted at a particular home does not violate the First Amendment. That’s because such a law would be “content neutral” — applied equally to not just all points of view but all topics as well. The court stressed that protesters do have the right to march through the area if they don’t stop in front of a particular home.

The court has also upheld a restriction on targeted picketing “before or about the dwelling or residence of a person,” wording nearly identical to Virginia’s statute, though the actual parameters of what that means — including an acceptable distance — have varied according to the situation.

Limits on free speech

Of course, there are certain defined exceptions to the First Amendment including speech that incites others to engage in imminent lawless violence, using fighting words to provoke others into a violent response or making true threats to another person. Someone could be arrested the moment they cross any of these lines.

The fact that these are federal judges introduces another limitation. There is a federal law that prohibits attempts to interfere with the administration of justice or attempts to influence the outcome of a particular case either by protesting in or near a courthouse or the residence of a judge or by using some form of sound enhancement.

Similarly worded state laws regarding protests outside of courthouses have been upheld as a means of ensuring a fair, nonpolitical outcome in pending cases. It’s not hard to assume that a court would reach the same conclusion regarding the leak-related protests.

More: The Roe v. Wade Leak Shows the Benefit of a Free Press

It seems protesters are at risk of arrest. Whether they could be convicted would remain to be seen. They could argue the decision is a foregone conclusion, and they were simply angry with the result, not seeking to change a particular justice’s mind. They could also argue that the now 70-year-old law clearly isn’t enforced every time someone protests at the Supreme Court building or a justice’s home, so their arrest was a case of selective enforcement.

In the interest of free speech, let’s hope it never comes to this. Despite requests from the governors of Maryland and Virginia for enforcement of the federal statute, every effort should be made — by protesters and law enforcement alike — to maintain peaceable assembly.

Kevin Goldberg is First Amendment specialist for the Freedom Forum. He can be reached at [email protected].

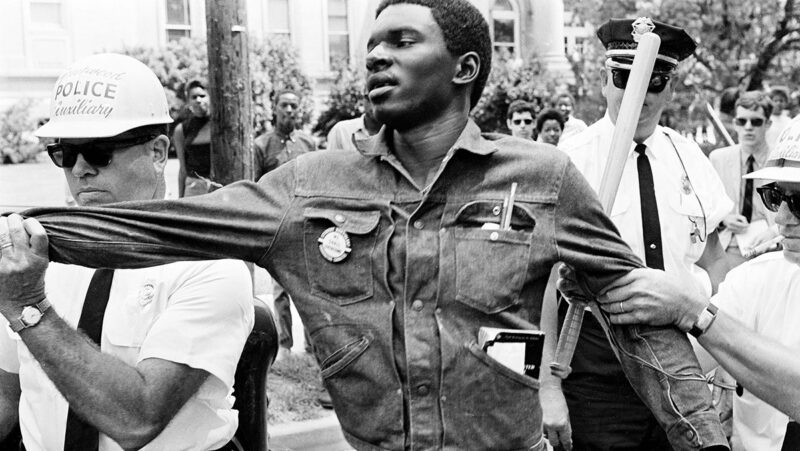

1968 Democratic National Convention Protests: A Look Back

Related Content

$30,000 Giving Challenge

Support the Freedom Forum’s First Amendment mission by Dec 31st and double your impact.