Unforgettable Stories and Images from Freedom Summer 1964

In the summer of 1964, more than 1,000 volunteers and activists went to Mississippi to register Black voters who were often denied access to the ballot box and other civil rights. The Freedom Summer 1964 campaign of voter education and registration was organized by groups including the Congress of Racial Equality and the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee.

Photojournalist Ted Polumbaum captured images of the campaign. He covered the Freedom Summer campaign for Time magazine, spending a month with the volunteers. The images are now part of Freedom Forum’s Newseum Collection.

Freedom Summer 1964 volunteers included college students, teachers, clergy, lawyers and activists who attended training sessions in Ohio before traveling by bus to Mississippi, where they defied segregation in a door-to-door campaign to register Black people to vote. The volunteers also set up community centers and taught thousands of children in Freedom Schools.

The campaigners exercised First Amendment freedoms to draw attention to the issue and to advocate for change – and faced threats to their rights and their lives. Volunteers were arrested and beaten. Three of the young activists were killed.

Credit for all images: Ted Polumbaum / Freedom Forum’s Newseum Collection

Freedom Summer 1964: Voting rights volunteers face violations of their freedoms – and violence

Activist Robert “Bob” Moses, head of the Freedom Summer project (left, in overalls and glasses), and John Doar of the U.S. attorney general’s office for civil rights (far right) spoke with about 1,000 volunteers assembled at two weeklong training sessions in June 1964. Doar warned volunteers that the campaign would be dangerous.

During training at Western College for Women (now part of Miami University) in Oxford, Ohio, before the Mississippi campaign, volunteers prepared for violations of their First Amendment rights to speech, assembly and petition, including jail and beatings. They learned self-defense and peaceful protest techniques. Here, some volunteers curl up on the ground.

“By the end of [training in] Oxford, if I wasn’t prepared to die, I at least was ready to be beaten up.” – Freedom Summer 1964 volunteer Paula Pace

Freedom Summer 1964 volunteers lived, worked and prayed together. But there were also disagreements about tactics and the motives of fellow volunteers. Some went because of their religious beliefs while others were opposing their parents or trying to fit in. The group also experienced racial tension and sexual harassment of women volunteers. In this image, volunteers with the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee stand near a table of food at a picnic in July 1964.

“[T]hat summer held promises. Some ominous. Some bright.” – Photographer Ted Polumbaum

Volunteers joined hands while standing beside their bus to sing the hymn “We Shall Overcome” before boarding to depart training in Ohio for Mississippi.

Freedom Summer volunteer teachers set up about 40 Freedom Schools teaching more than 3,000 Black students. Classes, like the one pictured above, were held after the regular school day at community centers like this one in Canton, Mississippi, which volunteers set up in homes and churches.

Community centers set up by Freedom Summer 1964 volunteers, like this one in Canton, Mississippi, in which a white volunteer and Black female students browse shelves of books, included libraries for Black children to access information at a time when schools were segregated, and many Black schools lacked resources. At Freedom Schools, students wrote poems, performed plays and produced newspapers.

“I am very little, and my skin is black. But I think I am still a citizen of Hattiesburg.” – Freedom School student in the school’s newspaper

Over four months during Freedom Summer 1964, four Black churches were burned, like this burned church in front of which a child stands, according to Polumbaum’s notes, with later counts putting the total closer to 20. Three volunteers who went to investigate one such incident disappeared.

Freedom Summer volunteers Michael Schwerner, James Chaney and Andrew Goodman disappeared near Philadelphia, Mississippi, while investigating the arson of a Black church. Volunteers searched the area, walking through the woods to look for them. They were later found shot and buried; their car burned.

“They were told … You are going to be jailed, you are going to get beaten, you are going to get shot. They were told: some of the people here are going to die this summer. Three did.” – Photographer Ted Polumbaum

Rabbi Arthur J. Lelyveld, pictured laying injured in a hospital bed with a bandage on his forehead, was sent by the National Council of Churches to support the Freedom Summer campaign. He was beaten along with two other volunteers while canvassing for voting rights.

Freedom Summer 1964 volunteer David Owen continued canvassing for voting rights after an attack left him injured and missing a patch of hair on his head. “I thought it would happen to someone, and I was ready for it, but I really didn’t think it would happen to me,” Owen told Polumbaum.

“We had been trained never to abandon one another. … I remembered I was pledged to nonviolence and if the rabbi wasn’t going to defend himself, I couldn’t.” – Freedom Summer volunteer David Owen

In cities throughout Mississippi, Freedom Summer volunteers assembled with locals to protest voting restrictions, including a woman who held a sign that reads “The Vote Shall Make Us Free." Federal law prohibited interference with people trying to vote, but Black voters in Mississippi were required to complete a three-page application with questions about the Mississippi constitution and citizens’ duties, followed by a waiting period and, frequently, denial of the application.

“I was born in this country, I lived in this country, I worked in this country 65 years. 65 years a citizen, and they won’t let us vote.” – A resident of Greenwood, Mississippi

Mississippi children, like this group of children posing with notes featuring messages in support of voting rights and Freedom Schools pinned to their clothing, assembled and petitioned for change during Freedom Summer 1964 alongside adults, despite the danger.

Protester Annie Lee Turner, 15 years old and pregnant, is dragged across a brick sidewalk by Greenwood Police Officer "Slim" Henderson during a voting rights demonstration on July 16, 1964, in Greenwood, Mississippi.

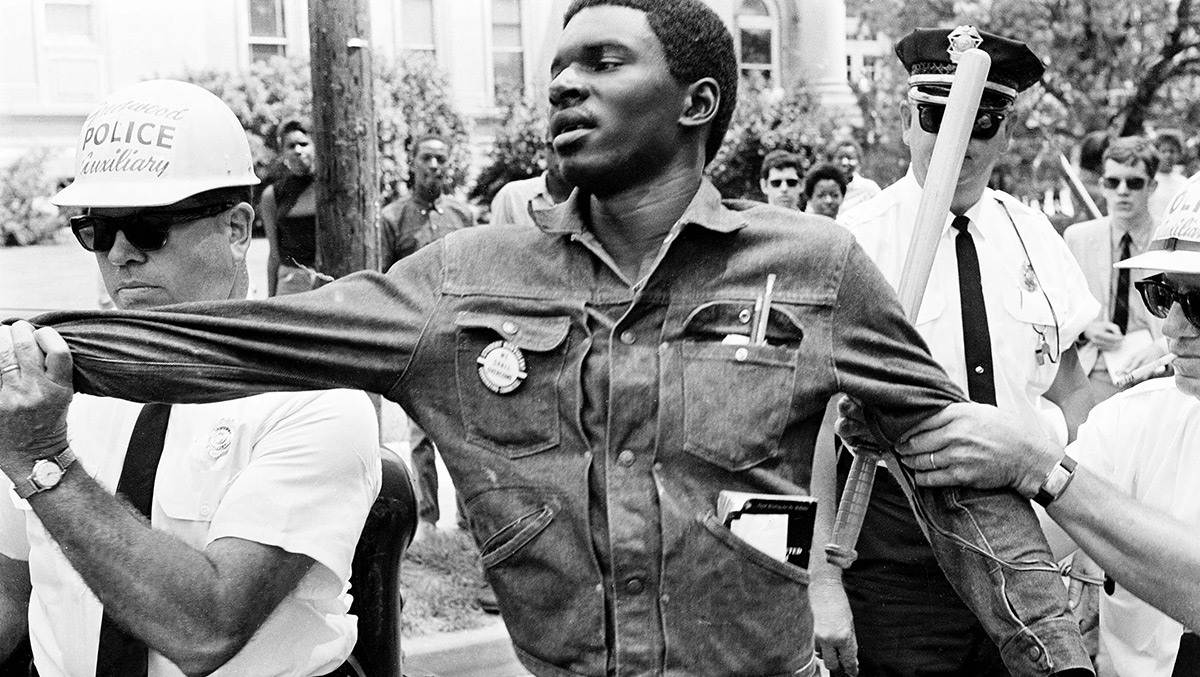

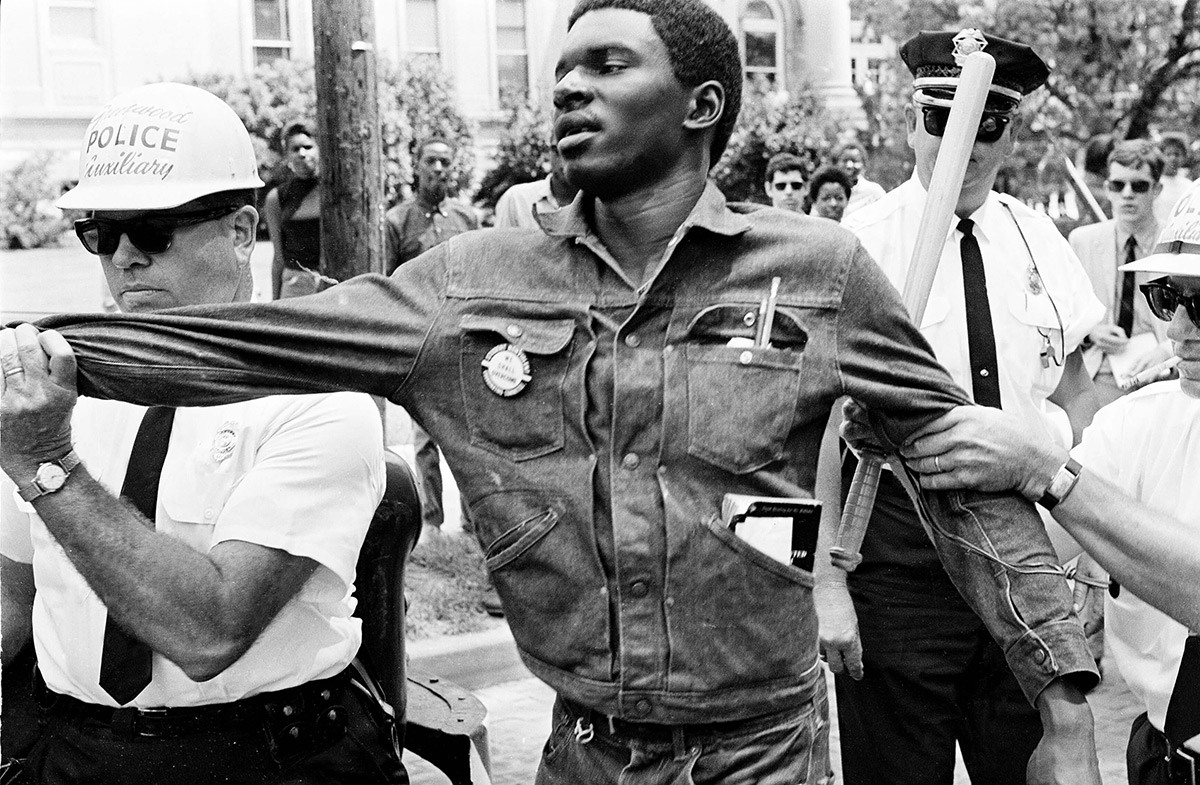

During the Greenwood protest, SNCC organizer Monroe Sharp was arrested by two policemen for assembling and petitioning for change. SNCC tactics included more direct action and protest, which was often riskier than the in-home organizing of other groups participating in Freedom Summer 1964.

More than 100 people, including the demonstrators pictured here stepping into a police wagon outside the Leflore County Courthouse, were arrested during a voter registration drive in Greenwood, Mississippi, on July 16, 1964. Mass arrests generated national attention to the Freedom Summer campaign and put pressure on federal authorities to enforce constitutional and civil rights laws.

Freedom Summer volunteers went door-to-door encouraging residents to try to register to vote, including this group of residents lined up outside the Leflore County Courthouse in Greenwood, Mississippi, on July 16, 1964. In some towns, volunteers had to register and be photographed by the police.

“The young civil rights workers and volunteers had come to Mississippi to do a job that the federal government had refused to do: to enable United States citizens (Black) to exercise their right to vote, to assemble, to express themselves.” – Photographer Ted Polumbaum

Freedom Summer 1964: Using and defending First Amendment Freedoms

A diverse group of Freedom Summer volunteers came together for a few months in 1964, uniting amid their differences in belief and views on organizing tactics. They spoke up in defense of Black Mississippians’ rights to practice their religion and to assemble without fear of violence that was tacitly supported by local law enforcement. Volunteers assembled and petitioned for equal voting rights, despite scrutiny from local government authorities, arrests and violence. By exercising and defending First Amendment freedoms, volunteers protected these freedoms for future generations.

About Ted Polumbaum

During his 40-year career, freelance photojournalist Ted Polumbaum (1924-2001) photographed newsmakers and events including the 1965 rematch between boxers Muhammad Ali and Sonny Liston; the political career of Ted Kennedy from 1958 to 1969; chef Julia Child in her kitchen; the 1967 Boston Red Sox “Impossible Dream” team; anti-Vietnam War protests in Washington, D.C., and Massachusetts; and civil rights leaders Andrew Young and Ralph Abernathy at the 1968 Poor People’s Campaign march from Mississippi to Washington, D.C.

His coverage of historic moments and extraordinary people included travels to China, Chile, India and Kashmir; politics, sports and celebrities; the hula hoop craze and Coney Island.

All of Polumbaum’s 200,000 photos are part of Freedom Forum’s Newseum Collection and can be licensed for use by filling out and submitting our Image License Request form.

What Is a Gag Order? Definition, Examples and More

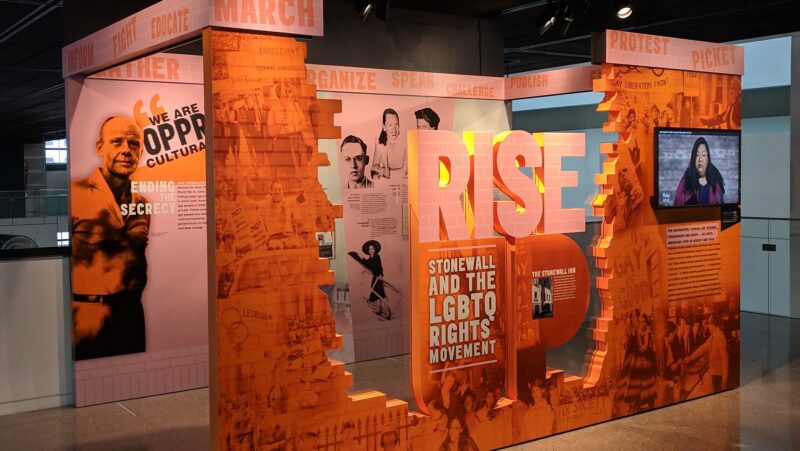

LGBTQ Activism: 5 Must-Know Stories

Related Content