Can Rap Lyrics Be Used as Evidence in Court? A First Amendment Analysis

The trials of rappers Young Thug (pictured above) and Gunna have generated significant controversy, especially within the rap music community. The two were indicted on racketeering charges. Young Thug and Gunna are two of 28 members of the YSL gang who were indicted on these charges stemming from alleged gang activity, murder, firearms and drug violations. The connection between the rappers and the gang was made, in part, on a mix of rap lyrics and social media posts. Gunna pled guilty to one charge and was given a five-year sentence, which was suspended subject to probation, and 500 hours of community service. Young Thug’s trial began in early 2024.

This sparked discussions about whether the rappers – and rap music generally – were being singled out by having their lyrics introduced into evidence. It also raised questions about unfair treatment based on their race. But highlighting their lyrics raised First Amendment concerns because prosecutors were seeking punishment based as much on their creative expression as their actual involvement in any criminal actions

This isn’t a new issue. It’s been happening for decades.

Today, Snoop Dogg is a household name. After a successful rap career, Snoop, whose real name is Calvin Broadus, became an entrepreneur and promoter of high-profile products, some produced in an “odd couple” pairing with Martha Stewart.

He came close to a very different life: In 1996, Broadus was tried for murder after a man was shot by his bodyguard. At his trial, the prosecution tried to use one of Snoop’s most popular songs, a collaboration with fellow rapper Dr. Dre called “Deep Cover,” to demonstrate Broadus’ criminal nature, based in part on the lyric “’Cause it’s 1-8-7 on an undercover cop.” 187 is California’s criminal code for murder.

But Calvin Broadus is a real person, and Snoop Dogg is a fictional persona created for artistic and entrepreneurial purposes. And Snoop’s song “Deep Cover” was the title song on the soundtrack of a 1992 movie of the same name about an undercover police officer. Snoop Dogg’s lyrics were introduced into evidence to demonstrate that he and the bodyguard initiated the confrontation that led to Philip Woldemariam’s death. Broadus was acquitted when a jury agreed that his bodyguard, McKinley Lee, acted in self-defense after Woldemariam reached for his gun.

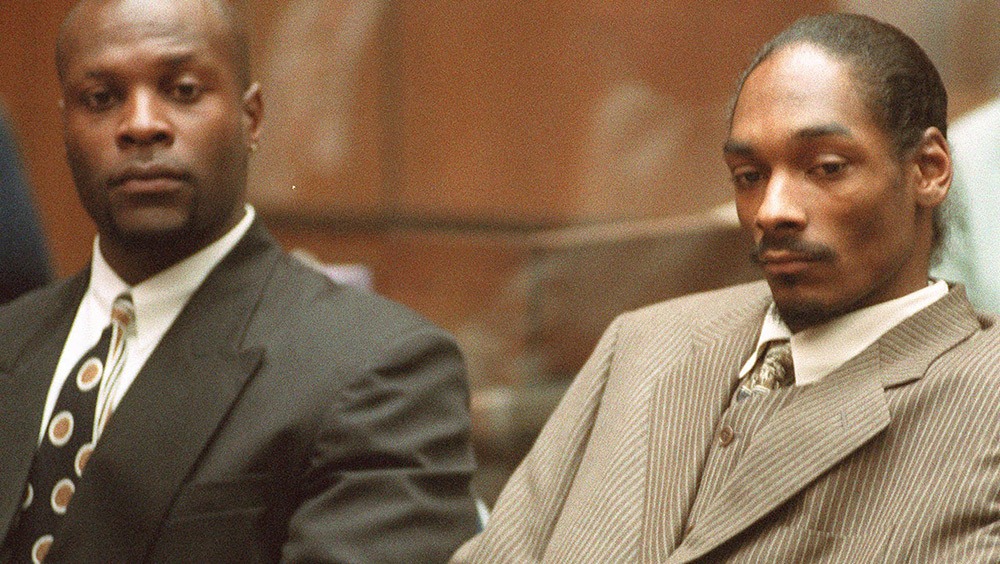

Snoop Dogg, whose real name is Calvin Broadus, right, and bodyguard McKinley Lee listen in a Los Angeles courtroom as they were acquitted of murder charges.

Snoop Dogg is perhaps the most famous rapper to have his lyrics used against him in a criminal trial. But he is hardly the only one.

Andrea Dennis, a University of Georgia law professor who co-authored a book titled “Rap on Trial: Race, Lyrics and Guilt in America,” has found at least 500 instances when rap lyrics were used as evidence in criminal cases.

Rap, like all forms of music, is protected as free speech. There is significant debate about whether using rap lyrics as evidence violates the First Amendment by punishing a particular form of creative expression.

Can rap lyrics be used as evidence in court without violating the First Amendment?

Rap lyrics can be used if the lyrics are actual evidence of the crime for which a person is on trial and do not lead the jury to create a false impression about the defendant on trial.

All federal and state criminal trials are governed by rules of evidence that say what can and cannot be introduced by prosecutors seeking to show a defendant is guilty (and by a defendant seeking to prove their innocence). Most exclude evidence that is “unduly prejudicial.” The judge will look at whether the evidence in question is directly relevant to the crime that was allegedly committed or whether it is being introduced to give the jury an unfavorable impression of the defendant.

When it comes to rap lyrics, a judge is more likely to allow the lyrics as evidence when they demonstrate a connection to the alleged crime. For instance, if the lyrics describe the exact scenario in which the crime happened, refer to the victim, or otherwise establish a motive or intent to commit the crime, they are more likely to be admitted. But if those details don’t match up, the judge is more likely to prevent the lyrics from being introduced because a jury would form an unfairly biased impression of the defendant that has nothing to do with their guilt or innocence, in effect putting artistic expression on trial.

Here are some examples of how that test has been applied in practice:

- In 1991, federal prosecutors in Illinois tried to prosecute rapper Derek Foster for possession and intent to distribute drugs found in his suitcase. At trial, the rapper claimed no knowledge of what was in the suitcase. Prosecutors introduced his lyrics into evidence: “Key for key. Pound for pound. I’m the biggest dope dealer, and I serve all over town.” Because he had a substantial amount of drugs in a suitcase, the lyrics were deemed relevant and introduced into trial. Foster was convicted.

- In 2008, rapper Vonte Skinner was found guilty of attempted murder. At trial, a police officer read 13 pages of handwritten rap lyrics taken from one of Skinner’s notebooks. But they had no relationship to the shooting Skinner was accused of; they were written several years earlier. Yet Skinner was convicted and sentenced to 30 years in prison. This was overturned on appeal when the New Jersey Supreme Court held that the lyrics should not have been used as evidence, saying, “The admission of defendant’s inflammatory rap verses, a genre that certain members of society view as art and others view as distasteful and descriptive of a mean-spirited culture, risked poisoning the jury against the defendant.”

- Even though it acknowledged that the lyrics of Lawrence Montague contained no specific details linking him to a 2017 killing, the Maryland Court of Appeals upheld their use in convicting Montague for that crime. The court allowed the use of the lyrics in part because the lyrics were viewed as an attempt to intimidate the sole witness who would testify against Montague. Montague recorded them while in jail awaiting trial and had a friend upload them to Instagram.

When applied correctly, the use of this balancing test does not violate the First Amendment. That’s because the court isn’t punishing rappers for their lyrics as creative expression. The court is simply acknowledging that they are important in establishing that person’s guilt or innocence.

What about non-rap lyrics?

The problem is that this balancing test is not always applied evenly. For several reasons, rap lyrics are introduced as evidence in criminal cases far more frequently than lyrics from other genres of music.

In an article published in The New York Times in 2022, Jaeah Lee wrote:

"The small number of non-rap examples that I found — only four since 1950 — involved defendants whose fiction writing or lyrics were considered to be evidence of assault or violent threats. Three of those cases were thrown out; one ended in a conviction that was overturned."

Why are rap lyrics used as evidence so much more than other types of music?

Rap is a genre that often includes first-person depictions of crime and violence to paint a vivid picture. The rapper may be telling a story they know, or they may choose to portray themselves in this manner because that’s what the audience expects. Or they are intentionally lashing out at perceived oppressors, including law enforcement.

As rapper Drakeo the Ruler explained to The Guardian:

“The whole point of me starting to rap is I get to rap and talk about these things and not do these things. And what would you rather, me rapping about stuff that I’m not actually doing, or out there doing it? It’s not real. Rapping is rhyming and pretending. It’s a persona.”

But the same elements of a successful rap song can be elements of a successful prosecution. Several studies have demonstrated a negative association with rap. In a 1999 study conducted by a California State University professor, subjects were given the hypothetical biography of an 18-year-old Black male accused of murder. Some were shown rap lyrics and told they were written by that same person, while others were not. The ones who were shown his rap lyrics were more likely to believe he committed the murder than those who were not.

This disproportionate treatment raises significant First Amendment concerns because political speech has the strongest protection under the First Amendment – and rap music is often political. Artists like Afrika Bambaataa, N.W.A., Queen Latifah, Public Enemy, Kendrick Lamar, De La Soul, Lauryn Hill, A Tribe Called Quest and others intentionally infuse their lyrics with social commentary designed to not only entertain but also to educate, to inspire, to motivate and to elicit change.

Kendrick Lamar performs at FYF Fest at Exposition Park in Los Angeles in 2016.

Yet the political and artistic elements of rap lyrics are often ignored, with prosecutors treating the words in an entirely literal sense in courtrooms. Using rap lyrics in this way raises First Amendment concerns because it punishes artistic expression based solely on its content, without any justifiable reason.

Examples of rap lyrics used as evidence

As a result, rap lyrics continue to be used in evidence, including in recent cases:

- In 2000, McKinley Phipps Jr., whose stage name is Mac Phipps, was getting ready to perform at a New Orleans venue when a 19-year-old was shot and killed. Phipps was tried for murder even though there was no physical evidence he was involved. Lyrics from his song “Murder, Murder, Kill, Kill” were introduced as evidence to demonstrate a violent lifestyle. He was convicted of manslaughter and sentenced to 30 years in prison, though he was granted clemency by the governor of Louisiana after 21 years.

- In 2016, rapper Tommy Mundswell Canady had the lyrics from his song “I’m Out Here” introduced into evidence in his murder trial after the victim’s father brought it to prosecutors’ attention. Canady said that the lyrics were heard incorrectly and did not match the circumstances of the murder. While in jail awaiting trial, Canady also wrote lyrics to pass the time, only to have a cellmate turn them over to the police because they referenced “shooting people.” In other lyrics, Canady lamented the “killing for no reason” he saw all around him. Sentenced to life in prison, he maintains his innocence.

- Drakeo the Ruler was charged with murder, conspiracy to commit murder, criminal gang conspiracy and illegal possession of a firearm after a murder outside a party in Los Angeles in 2016. Investigators acknowledged that Drakeo was not directly involved; in fact, someone else confessed to the killing. But prosecutors also knew that a friend of Drakeo’s confessed to firing some shots and said that Drakeo’s rap crew was a “criminal gang” involved in the killing, with Drakeo as the head of that gang. They found a music video made by Drakeo that featured the friend involved in the shooting holding the gun used in the shooting. They showed it to the jury along with lyrics about driving around with another rapper “tied up in the back” of the car, as a means of suggesting to the jury that the murder was the result of a missed attack on that rapper. Drakeo was acquitted.

Can lyrics themselves be criminal?

Lyrics themselves can be criminal when they fall into a category of expression that is unprotected by the First Amendment. This most often happens when lyrics are true threats. In 2023, the Supreme Court offered more protection for those accused of making true threats. In Counterman v. Colorado, Billy Counterman sent hundreds of threatening messages to musician Coles Whalen, putting her in fear for her life – something Counterman said he never intended. The Supreme Court ruled in Counterman’s favor, saying that a true threat only exists when the speaker intends to make or should have known that the subject would fear for their safety. In the context of music lyrics, this means that the songwriter or rapper must direct those lyrics toward a certain person, wanting – or least knowing – the subject would be afraid.

Laws proposed or passed to protect rap lyrics from being used as evidence

Concerned with the threat to free expression posed by using rap lyrics as evidence in criminal cases, two state legislatures and the U.S. Congress have taken steps to limit this practice:

- On January 1, 2023, the “Decriminalizing Artistic Freedom Act” went into effect in California. This law requires prosecutors who want to admit artistic expression, including rap lyrics, to prove the relevance of the evidence in hearings that occur without the jury present.

- The New York State Senate passed “Rap Music on Trial” legislation in 2023. It requires prosecutors to prove that rap lyrics are “literal, rather than figurative or fictional” before they can be admitted as evidence, putting the burden of proof squarely on the prosecution. It did not pass the New York State Assembly.

- The “Restoring Artistic Protection” Act or RAP Act was introduced in the United States House of Representatives in 2022. The bill says that lyrics may only be admitted into evidence if they have a “literal meaning” as determined by specific references to the alleged crime or value not provided by other existing evidence. It was reintroduced in 2023. Neither version was voted on by the House.

These bills reflect the need to protect artistic expression across all music and other forms of creative expression. The federal legislation was supported by an open letter published in The New York Times and Atlanta Journal-Constitution that was signed by more than 100 artists, including Drake, Megan Thee Stallion, John Legend, Coldplay, 50 Cent and Morgan Wallen, as well as several free expression organizations and music companies. The letter says, in part:

“Rappers are storytellers, creating entire worlds populated with complex characters who can play both hero and villain. But more than any other art form, rap lyrics are essentially being used as confessions in an attempt to criminalize Black creativity and artistry.”

PROTECT BLACK ART

— YOUNG STONER LIFE (@YoungStonerLife) June 30, 2022

A petition has also been circulated by hip-hop executive Kevin Liles, who summarizes the importance of protecting rap lyrics as expression, saying:

“This practice isn’t just a violation of First Amendment protections for speech and creative expression. It punishes already marginalized communities and silences their stories of family, struggle, survival, and triumph.”

Kevin Goldberg is First Amendment specialist for the Freedom Forum. He can be reached at [email protected].

Hair and Free Speech: Can Employers, Schools Regulate Hairstyles?

Perspective: Tide May be Turning Toward Religious Exemptions From Vaccine Mandates

Related Content

$30,000 Giving Challenge

Support the Freedom Forum’s First Amendment mission by Dec 31st and double your impact.