Perspective: Is the Supreme Court Still a Defender of Press Freedom?

For decades, the Supreme Court has interpreted the First Amendment as the protector of the nation’s news media:

- In New York Times Co. v. Sullivan in 1964, the court made it easier for journalists to criticize public figures without being sued.

- In a 1967 case that applied the Times v. Sullivan precedent more broadly, Justice William Brennan Jr. embraced “the indispensable service of a free press in a free society.” He once stated that, “From the First Amendment, all our liberties flow.”

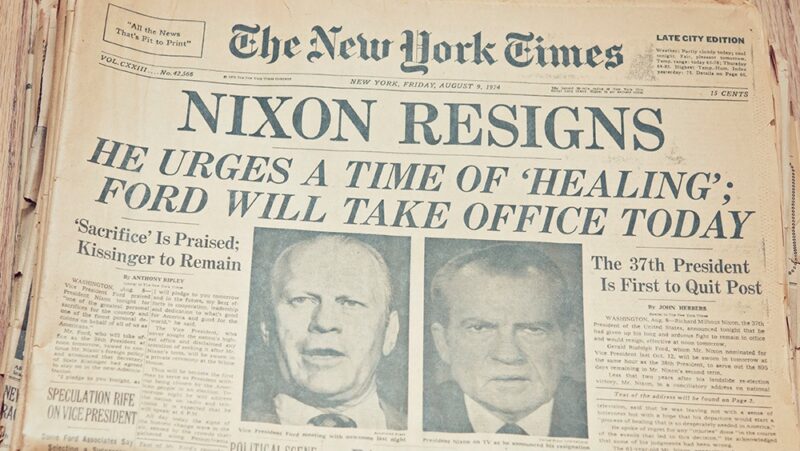

- When the Nixon White House tried to block the reporting of secret documents about the Vietnam War in 1971, the court said no. “To find that the President has ‘inherent power’ to halt the publication of news,” Justice Hugo Black wrote, “would wipe out the First Amendment.”

- In Reno v. ACLU, a 1997 case, the court gave its blessing to the internet as a media outlet, likening it to a colonial “town crier” whose communications were protected by the First Amendment.

But the golden era of Supreme Court protection of the press may be waning, according to a new study.

Court Talks Press Less

First Amendment scholars RonNell Andersen Jones of the University of Utah S.J. Quinney College of Law and Sonja West of the University of Georgia School of Law analyzed thousands of the Supreme Court’s decisions to tally justices’ depictions of the press going back as far back as 1784. The surprising result: the court’s mentions of the press have dropped sharply in numbers, and when the justices do discuss the media, it is more often with negativity, not respect.

“Our data suggest that any hopes that the judiciary can be trusted to be a savior of press freedom might be misplaced,” Jones and West wrote. “The U.S. Supreme Court is giving much less consideration to the press and its freedom than it did a generation ago, and increasingly does not think well of it.”

One troubling data point is that the phrase “freedom of the press,” often used in the 1960s and 1970s in First Amendment cases, is almost nowhere to be found in recent years. “Rhetorically, the freedom of the press as a specified, recognizable liberty has all but disappeared,” the scholars wrote.

“The conventional wisdom prior to this study was that the press assumed that the court was a consistent and reliable supporter of the press. An important first step for the press may be to realize that this is not the case. Press positivity at the Supreme Court is not something the press should take as a given.” – RonNell Andersen Jones, First Amendment scholar, University of Utah S.J. Quinney College of Law

Tone Toward News Takes a Turn

As someone who has covered the Supreme Court for more than 40 years, I can safely say that personal interactions between the press and Supreme Court justices have not always been warm. In the mid-1990s, Chief Justice William Rehnquist once said to a group of reporters, including me, at a social event, “The difference between us and the other branches of government is that we don’t need you people of the press.”

Recent mentions of the press in Supreme Court opinions have often been disparaging. As The New York Times noted in April, Justice Anthony Kennedy in 2010 spoke of “the decline of print and broadcast media.” In a 2019 dissent on a criminal case that had received widespread press attention, Justice Clarence Thomas said, “The media often seeks ‘to titillate rather than to educate and inform.’”

Press Protections at Risk

Thomas is riding the anti-press wave most aggressively. In two recent cases in which Thomas disagreed with a majority of the court, he has made it clear that he believes Times v. Sullivan should be overturned. That decision, which makes it almost impossible for public officials to sue the media for libel, is probably the most important press-protective ruling the modern Supreme Court has issued, but Thomas views it as “policy-driven” and “masquerading as constitutional law.” He’s not the only judge to express this sentiment.

In March, Laurence Silberman, an influential appeals court judge, referenced Thomas’s comment in disagreeing with a ruling throwing out a libel suit, asserting that the Sullivan decision was “profoundly erroneous” and should be overturned.

Retired federal Judge J. Michael Luttig responded, saying Silberman’s dissent was “an opportunity for score-settling with the Supreme Court and the nation’s media.” Luttig added that Times v. Sullivan was part of “the bulwark of the First Amendment and American democracy.”

Times v. Sullivan

The unanimous Supreme Court ruling in Times v. Sullivan, a critical case in the civil rights movement, is that citizens have a First Amendment right to criticize government officials. The court ruled that freedom of the press protects statements about the conduct of politicians. It found that public officials who sue for libel must meet a high standard of proof: showing those statements are made with actual malice.

Repealing Times v. Sullivan would open the door to a barrage of baseless lawsuits from government officials and public figures that could cripple the news media. The late journalist Anthony Lewis wrote in 1983 that press freedom would be hampered by “the cost of defending libel actions: the cost not only in money but in time and in the psychological burden on editors and reporters.”

Before she joined the Supreme Court, Justice Elena Kagan wrote that libel lawsuits against the media, like the one at issue in the Sullivan case, were “not attempts by individuals to redress damage to personal reputation, but rather were attempts by government to shut down criticism of official policy.”

Even if news stories are sometimes caustic, as Brennan said in the Sullivan decision, “debate on public issues should be uninhibited, robust and wide open.”

Tony Mauro is a fellow for the First Amendment at the Freedom Forum. He has covered the U.S. Supreme Court since 1979 including for the National Law Journal and ALM Media Supreme Court Brief.

Freedom of the Press Examples You Should Know

Related Content