Freedom of the Press Examples You Should Know

While anyone can choose to be a journalist – a member of “the press” – most people don’t work in journalism or even in the much broader catch-all “the media.” But even if you don’t personally work as a journalist (however broadly you define that), you benefit from freedom of the press in having access to so much information.

Despite its prominent place in the First Amendment, there’s no real definition in the Constitution for “the press.” Indeed, that vagueness is a good thing. Imagine if the First Amendment only covered broadsheet pamphlets, the dominant “press” of the time when the 45 words were written.

What this means today is that anyone and everyone can be a journalist or otherwise receive free press protections by writing online or self-publishing a book. There’s no such thing as a government license for journalists like there is for barbers, doctors, lawyers and some other professions.

This doesn’t mean journalists can do and say anything they want without consequence. Defamation and libel laws can and do apply to journalists. A journalist who lies about their sources, plagiarizes someone else’s work, or commits a crime can face legal and professional consequences.

In this post, we explore freedom of the press examples from throughout history, highlight examples of past and current challenges to press freedom, and more.

Freedom of the press examples from throughout history

Finding freedom of the press examples is almost like trying to count every grain of sand on a beach. Every day in the U.S., there are countless examples: Whenever a reporter covers a protest that shuts down city streets, or a news outlet publishes an investigation of public corruption, or a local online news outlet updates its community calendar, these are examples of freedom of the press in action.

Here are some examples of moments and people who shaped what press freedom is and how we understand it today.

Early challenge: Sedition Act

The First Amendment was still fresh when U.S. press freedom came under fire from the government. In 1798, Congress passed four laws known collectively as the Alien and Sedition Acts. The fourth of those, the Sedition Act, made it a crime to publish “any false, scandalous and malicious writing.” The law empowered the government to jail newspaper editors and others who criticized President John Adams and his administration. About two dozen people, most of them newspaper printers, editors and writers, were arrested under the law. The Sedition Act, which had been favored by Adams and opposed by Thomas Jefferson, expired the day before Jefferson took office as president in 1801. Jefferson pardoned those convicted under it.

Pioneering coverage: Ida B. Wells and Ida Tarbell

Though journalism in the U.S. was long dominated by men who excluded women from working in newsrooms, there are prominent examples of trailblazing women journalists whose contributions to the field set the tone for press freedom today. Sometimes this required people starting their own newspapers or pamphlets – using their press freedom – to literally start their own presses.

Two examples are from “the two Idas”: Ida B. Wells and Ida Tarbell.

Ida B. Wells (aka Ida Bell Wells-Barnett) was born into slavery in 1862 and freed by the Emancipation Proclamation. Her coverage in the Memphis Free Speech and Headlight newspaper of racial segregation, the lasting effects of slavery, and unequal treatment of Black people in the country were influential in setting the tone for coverage of the same issues during the Civil Rights era nearly 100 years later. She documented lynchings and other mistreatment of Black people in her widely distributed pamphlet “Southern Horrors: Lynch Law in all its Phases.” Her pamphlet debunked narratives in the dominant white press that lynchings were solely done to Black criminals who had committed crimes against white people.

Born in 1857 at the beginning of the oil boom, Ida Tarbell didn’t see herself as a crusader or pioneer but rather as a historian. She was raised in Pennsylvania in the shadow of the U.S. industrial coal and oil fields. Her 19-part series “The History of the Standard Oil Company,” published in McClure’s Magazine over three years beginning in 1902, revealed oil tycoon and billionaire John D. Rockefeller’s monopolistic practices. Tarbell’s investigation ultimately led to new antitrust laws for the country that set the tone for today’s laws that regulate businesses against monopolistic practices.

New York Times Co. v Sullivan lawsuit

Journalists and news outlets can be liable for defamation. Many journalists have heard from someone (often elected officials) who didn’t like some way they were covered and threatened to sue. But the bar to find a journalist liable is high.

That high bar comes from the 1964 Supreme Court case New York Times Co. v Sullivan. The Times ran an advertisement from pro-Civil Rights activists. The ad contained several inaccurate statements, and a public official in Alabama sued the Times for libel.

The court sided with the Times, ruling they were not responsible for the inaccuracies in the ad. But the practical effect was much larger than the narrow case of an advertisement. It set the standard that’s still used today to measure how a journalist or news outlet can be liable for damages in defamation cases. The standard called “actual malice” means a public official bringing a lawsuit must prove the news outlet knew the information was false and published it anyway or acted with reckless disregard for the truth.

The standard doesn’t make it impossible to sue a journalist for defamation, but it does make it difficult.

Pentagon Papers leak

When Daniel Ellsberg leaked an internal government report to The New York Times, he probably had no idea he’d be discussed in college journalism classes decades later. His work with a government committee detailed the history of the U.S. military’s involvement in Vietnam. Ellsberg, who worked in the Pentagon and as a government contractor with the RAND Corporation, leaked the papers to the press, and The New York Times published them in 1971. The government report, which was not public until Ellsberg leaked it, showed President Lyndon Johnson had lied about military actions in Vietnam. It also outlined much more than the public was ever told about U.S. involvement in the region well before the Vietnam War began. Ellsberg was arrested and faced federal charges under the Espionage Act, but a federal judge declared a mistrial, and Ellsberg was never convicted.

Even though the Pentagon Papers reflected poorly on his Democratic predecessors, President Richard M. Nixon attempted to stop The New York Times from publishing additional documents related to the leaked report. The administration convinced a federal judge to impose an injunction on the Times to stop them from publishing more in the Pentagon Papers series. In 1971, the Supreme Court overturned the injunction, allowing the Times to continue publishing more from the leaked documents.

Watergate coverage

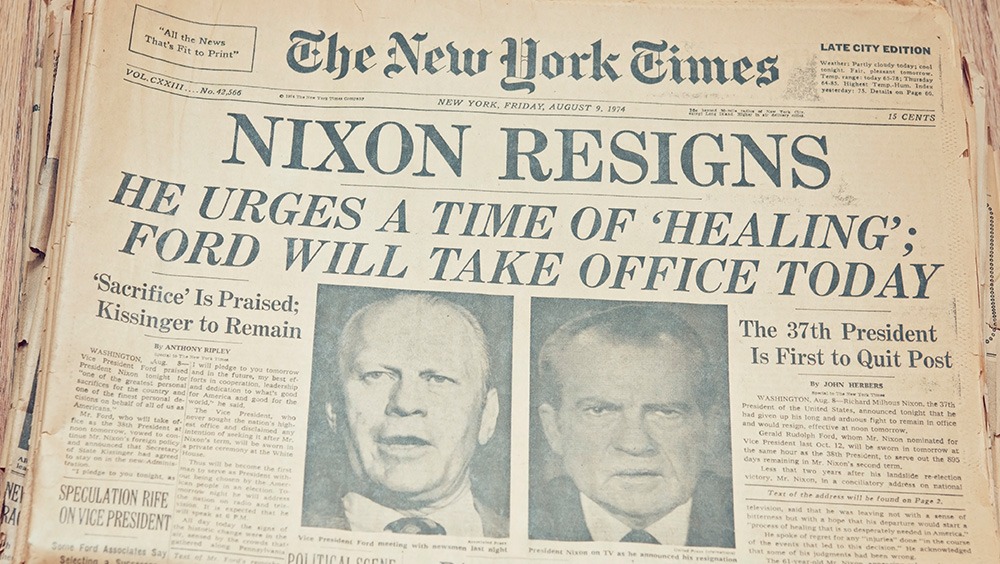

The break-in at the Democratic National Committee’s headquarters at the Watergate office building on June 17, 1972, didn’t attract a lot of press coverage at the time. Fifty years later, it is probably the most recognized example in U.S. history of how freedom of the press in action can have a huge impact. The Washington Post’s coverage won the Pulitzer Prize and launched the careers of reporters Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein into journalism celebrity status, inspiring the movie “All the President’s Men,” based on the journalists’ book of the same name. Their reporting helped prompt Congress to investigate President Richard Nixon, who resigned from office in August 1974 before he could be impeached.

Shifting era: Are bloggers part of ‘the press’?

With the late-’90s and early 2000s internet era came numerous examples of not just a shift in how news is delivered but who delivers the information.

The rise of blogging meant more people could enter journalism, much like the rise of the printing press meant anyone could print and distribute their own pamphlets. The connection is that the First Amendment prohibits laws that restrict freedom of the press, and it applies to people who are not working for traditional, large news outlets like The New York Times, The Washington Post or network TV news.

One person who famously capitalized on this technological shift is Matt Drudge, known for The Drudge Report, his widely popular and influential political news website. On Jan. 17, 1998, Drudge revealed that Newsweek had killed a story about a sex scandal involving President Bill Clinton and an intern. By breaking the Monica Lewinsky story, Drudge helped shift the balance of power between “old media” and “new media.” Even the government realized the importance of this new technology: The report on the official inquiry into the scandal was released online.

In the following years, journalism institutions like the White House Correspondents’ Association and various government bodies wrestled with whether “bloggers” and online-only outlets qualified as “the press” and considered how to issue them credentials to access meetings and news conferences.

Garrett Graff demonstrated this shift in credentialing and the question of who qualifies as a journalist. In 2005, Graff was a 23-year-old who wrote Fishbowl DC, a gossip blog about Washington, D.C., news media. He became the first blogger to get a White House press pass and access to the briefing room.

Examples of current challenges to freedom of the press

Anti-SLAPP legislation

Lawsuits can be filed, or just threatened, against anyone, including journalists. These suits often have the effect of stopping people from speaking or news outlets from publishing.

Such suits are broadly called a SLAPP: strategic lawsuit against public participation. Sometimes even the threat of being sued will keep a journalist from exercising their First Amendment-protected right.

Anti-SLAPP laws are meant to, well, slap back. They put limits on how such lawsuits can be filed and attempt to disincentivize lawyers from filing them in the first place by making them easier to dismiss.

As of September 2023, 33 states and Washington, D.C., have some form of anti-SLAPP statute, but there is no federal anti-SLAPP law.

Shield laws

There are bright spots and black holes when it comes to freedom of the press examples in the U.S. One bright spot is the ongoing effort to pass a federal shield law, which would protect journalists from being compelled to reveal their confidential sources. This is rare, but it comes up in cases involving leaks to news media, particularly involving national security cases.

Freedom Forum wrote in April 2023:

“Journalist groups have been pressing for more than 15 years for a federal shield law, formally called the Free Flow of Information Act. While there is no such federal law, every state except Wyoming has similar legal protections for journalists through laws or court rulings.

Despite bipartisan support, efforts to pass a federal shield law have come up short. Some journalists and free press groups have hesitated on the idea because it may require Congress to define who is and isn’t a journalist. That could lead to licensing of the press ...”

Freedom of the press examples are everywhere

Beside well-known examples like Watergate and the Pentagon Papers, there are numerous lesser-known instances of freedom of the press bumping up against public actions and creating tension between journalists and public officials.

From an Oregon reporter being arrested while covering a homeless encampment sweep in a public park to journalists being detained while covering protests and rioting in Ferguson, Missouri, to the 2023 raid on a Kansas newspaper, these and many other stories highlight instances when freedom of the press gets challenged.

The lack of specifics in the First Amendment with a mere four words – “or of the press” – can create tension between journalists and government officials and leaves open many questions for courts to interpret. It also allows so many people to work freely as journalists. It’s a job that anyone can do without government approval, thanks to the First Amendment and its guarantee to ensure a free and independent press.

Scott A. Leadingham is a Freedom Forum staff writer, journalist and journalism trainer. On Twitter/X: @scottleadingham

Meet Georgia, One of 42 Unique Professionals Stepping up for Their Hometown

What Is Defamation? Everything You Should Know

Related Content

$30,000 Giving Challenge

Support the Freedom Forum’s First Amendment mission by Dec 31st and double your impact.