Banned Movies: 20+ Films That Were Censored or Restricted

Since the invention of the moving picture, films have entertained, educated, inspired and sometimes horrified people.

From the beginning, some movies stirred controversy and calls for censorship. In 1915, the U.S. Supreme Court said that filmmaking was a business, not free speech, and cities and states banned movies as they saw fit.

In the 1930s, Hollywood studios were tired of their films being recut by different censorship boards around the country, so they started a voluntary code of self-censorship.

By 1952, the Supreme Court reversed its 1915 decision and protected most movies as free speech under the First Amendment – but not all. Some movies have still been banned.

With that being the case, we explore movies that have been banned, censored, challenged or restricted by the government, movie makers or critics – and when such bans violate the First Amendment.

Discover 20+ banned movies from throughout U.S. history

Almost as soon as there were movies, there was censorship. In 1896, the Catholic Church called for censorship of one of the earliest commercial films, a short called “The Kiss,” arguing that an on-screen kiss was immoral. In the early 1900s, other religious groups called for federal regulation of movies they found indecent. A censorship board that formed in New York pressured some movie theaters to close.

In 1915, the Supreme Court ruled 9-0 that movies were not protected by the First Amendment (Mutual Film Corp. v. Industrial Commission of Ohio), enabling state and local governments to set up film boards. These government film boards required licenses to show films and sometimes censored or banned movies.

City and state-banned movies

Censorship boards across the country banned movies for a variety of reasons.

One of the first widely banned movies in the U.S. was “The Birth of a Nation” in 1915. It was controversial for its portrayal of the Civil War, the post-war era and race. The NAACP led some efforts to ban it.

“Babe Comes Home” was banned in Chicago in 1927 for a scene portraying baseball star Babe Ruth chewing tobacco.

In 1931, the city of Riverside, California, banned “No Limit.” But it wasn’t banned due to its content. Clara Bow, the movie’s star, was present at the trial of a former employee who was charged with car theft. City officials didn’t want anyone associated with a crime on screens in their town.

Hollywood decided to censor itself

Producers in the growing movie industry did not like it when government censored or banned movies they made. It was expensive and time-consuming to get licenses everywhere they wanted to show a movie. Audiences saw different versions depending on what passed their local censors. The studios decided to set up their own system to review movies before they were released and potentially censored by the government. The Motion Picture Production Code was adopted in 1930. It made a list of voluntary rules for movies. It was commonly called the Hays code after Will H. Hays, president of the Motion Picture Producers and Distributors of America. The first movie censored by movie producers under the Hays code was “Tarzan and His Mate” in 1934. A nude swimming scene showing Olympic swimmer Josephine McKim, standing in for star Maureen O’Sullivan as Jane, was cut. The goal of this self-censorship was to ensure fewer government-banned movies.

The 1943 Italian film “Ossessione” was banned in Italy over its dark content. Nearly all copies were destroyed. It was banned in the U.S., too, but not over content. The film was based on the 1934 James M. Cain novel “The Postman Always Rings Twice.” By the time the film came to the U.S., an English version was already in the works. The film was banned over a copyright dispute.

Memphis banned “Brewster’s Millions” in 1945 because censors said an African American servant character had “too familiar a way about him.” The local censorship board complained that the picture presented “too much social equality and racial mixture.” “Curley” in 1947 and “Lost Boundaries” in 1949 faced similar bans for not meeting local segregation standards.

In 1948, the Supreme Court ruled that a few Hollywood studios had an illegal monopoly on movies (United States v. Paramount Pictures Inc.). Studios produced movies and owned the theaters that showed them. Ending this monopoly led to a flood of independent and foreign films, including controversial films that became banned movies.

One was “The Miracle,” an Italian film that features a woman with mental illness who believes she is the Virgin Mary. The movie includes themes of sexual assault and pregnancy. The Catholic Legion of Decency, a private film review organization, successfully petitioned for “The Miracle” to be banned in New York. But there was a dispute over which government body could censor the movie. (Remember, cities and states could make their own rules).

The case went all the way to the Supreme Court. Its decision: No one could ban the film. The landmark 1952 ruling (Joseph Burstyn Inc. v. Wilson) said movies were protected as free speech by the First Amendment. They couldn’t be banned just because some viewers might find them offensive. This reversed the 1915 ruling that had led to so many banned movies. But movie banning wasn’t over.

Obscenity – and obscene movies – are not protected as free speech under the First Amendment. In 1953, New Jersey banned “The Moon is Blue” for being indecent and obscene. The nature documentary “The Vanishing Prairie” was briefly banned in New York in 1954 over footage of a buffalo giving birth, but a successful petition saved the film. Nudist film “Garden of Eden” was banned in New York until a court ruled in 1957 that on-screen nudity was not automatically obscene. Movies with nudity were still banned elsewhere, though, as various courts up to and including the Supreme Court heard more cases related to obscenity and issued rulings that tweaked the definition and type of materials to which it applied. Examples include 1960’s “Hideout in the Sun” in Memphis and 1963’s “Promises! Promises!” in several cities.

In an unusual case, the 1967 movie “Titicut Follies” was banned in Massachusetts. The film included real footage of people at a prison. The footage violated privacy protections.

Hollywood replaces Production Code with MPA ratings

By this time, the Hays code had collapsed. Fewer filmmakers were opting to have their films reviewed – and potentially censored – by the independent group. Cultural standards for movies had changed. Most government censorship had been ruled illegal. In 1968, the code was replaced by an MPAA rating system similar to today’s MPA movie ratings. These labels are also voluntary and not connected to the government. But movie theaters generally agree to enforce private rules about access to PG-13 and R-rated movies, for example.

Artist Andy Warhol is known for his pop art paintings, but he also made “Blue Movie,” a 1969 film that was banned in New York for being obscene. That same year, the Supreme Court ruled (Stanley v. Georgia) that possessing obscene material like sexually explicit films in your own home is not illegal. But transporting it across state lines or showing it in theaters could be prosecuted.

The 1972 film “Deep Throat” enjoyed significant mainstream success. But the X-rated film was banned in 23 states, including New York. Showings had lines around the block, but many screenings were raided, and theater owners were fined, though some later won in court. Then-President Richard M. Nixon said about the film, “So long as I am in the White House, there will be no relaxation in the national effort to control and eliminate smut from our national life.”

The following year, the Supreme Court in an unrelated case more specifically and narrowly defined obscenity. But “Deep Throat” star Harry Reems still faced legal trouble. In the summer of 1974, Tennessee sought FBI help to arrest Reems. Movie stars Warren Beatty and Jack Nicholson agreed to testify on his behalf, but Tennessee wouldn’t let them in the courtroom. Reems was found guilty of conspiracy to transport obscene materials across state lines. He appealed, and the charges were later dropped.

The bans that weren’t

In 1979, a New Jersey citizens group petitioned the mayor of their town to ban “Monty Python’s Life of Brian,” calling it “an assault on all religions.” The petition failed. In 1988, city leaders in Savannah, Georgia, asked film company Universal Pictures not to show “The Last Temptation of Christ” over concerns about the treatment of religious content, but the film opened anyway.

Federal government-banned movies

Few movies have been banned by the U.S. federal government. But some have.

In 1948, the Federal Bureau of Narcotics banned a Canadian government-funded documentary, “Drug Addict,” for a portrayal of drug use that didn’t align with U.S. policy. The head of the bureau pressured the Canadian government into not distributing the film in the U.S. He later said that the MPAA, the private movie-industry ratings board, and not the government had banned the film, which the MPAA disputed.

The 1967 Swedish film “I am Curious: Yellow” was seized by the U.S. customs agency — physically preventing its distribution in the U.S. — and banned as obscene. A federal court ruled it was obscene, but an appeals court reversed the ruling, and the film became a hit in theaters.

In 1982, the U.S. Department of Justice ordered the distributors of the Canadian film “If You Love this Planet,” to register as foreign agents and required the film to carry a “political propaganda” label. The film featured an Australian anti-nuclear activist and included clips of then-President Ronald Reagan. The Department of Justice’s designations effectively limited distribution of the film. The distributors sued, saying the label was censorship that violated their free speech rights. They lost at the Supreme Court (Meese v. Keene) – but that didn’t stop the film from winning an Oscar.

The Federal Elections Commission in 2008 banned “Hillary: The Movie” from airing on cable TV in advance of the Democratic presidential primaries. The electioneering law the FEC cited in the ban was overturned by the Supreme Court in 2010 in Citizens United v. Federal Election Commission.

International pressure buries Disney film

The First Amendment protects most movies from government censorship in the United States. But countries around the world have different censorship laws. Those rules can affect movies made in the U.S. For example, in 1997, director Martin Scorsese made “Kundun,” a Disney-produced movie about the fourteenth Dalai Lama. The government of China strongly objected to the film’s contents. When Disney released the film, China banned all Disney media. Disney apologized and pulled the film from distribution.

Public school-banned movies

The First Amendment protects movies from most government censorship. And students at public schools do have free speech rights. But schools have broad leeway to choose what materials to show in class.

In 1987, a Utah school district banned an educational film about AIDS. The American Red Cross film discussed sex education topics that school officials found controversial. However, some other Utah districts showed the film to students with parental consent. In 1982, a St. Louis high school science teacher was forbidden from showing the 1960 film “Inherit the Wind,” which depicts the famous Scopes “Monkey” trial.

In 1985, a Michigan elementary school canceled free film showings at the county library over objections to PG- and R-rated selections. In 2007, school districts in Seattle and Colorado banned R-rated movies.

More recently, a Florida teacher faced investigation for potential violations of the Parental Rights in Education Act over a film choice. In May 2023, the fifth-grade teacher showed her students “Strange World,” an animated Disney film that includes a gay character. Another Florida school in March 2023 pulled the 1998 Disney movie “Ruby Bridges” from schools after a parent’s complaint. The movie tells the true story of one of the first Black students to integrate a public school in Louisiana in 1960.

Banned movies and the First Amendment

A complicated history of state-level censorship in the early decades of cinema led to Hollywood trying to censor itself rather than face government licensing and fines.

Since 1952, movies have been protected from most U.S. government censorship as free speech under the First Amendment.

Movies can still sometimes be banned if they fall into a category of unprotected speech, like obscenity.

Voluntary MPA ratings can help people choose which movies to watch or avoid based on their content, but the government cannot ban or censor movies based on their messages or viewpoints.

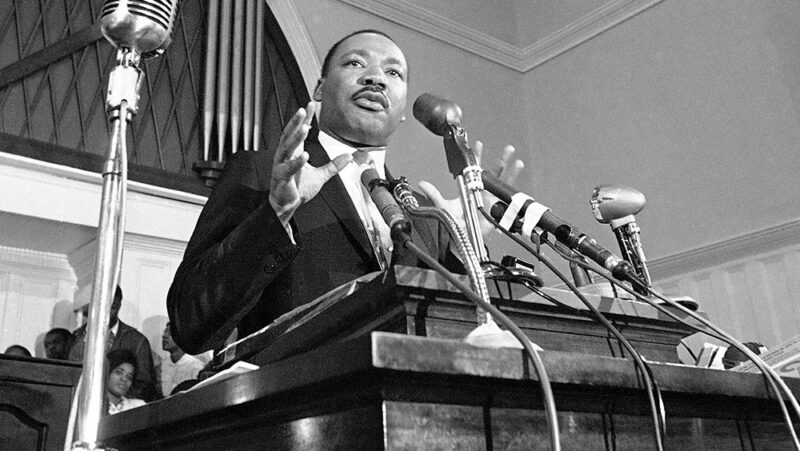

25 Black Civil Rights Activists Who Used the Power of the First Amendment

Watch: First Five Now: The Fight for Free Speech

Related Content