We Once Went “Mad” for the Magazine — and it was Fun and Funny

The world is a little bit less MAD — and the poorer for it.

The quintessential baby boomer-era satire mag, MAD magazine announced as of August 2019 it will contain only re-published content, on a monthly basis — industry-speak for trying to garner what nostalgia-tinged profits might still be obtained from those who recall better days.

Playboy, Rolling Stone and now MAD: The nameplates may remain on repurposed products and in digital or slicker formats, but as each announced its essential demise in the past year or so, the print-and-ink-on-paper soul of each, like Elvis, “has left the building”

The first two publications in that trio appealed, in very different ways, to the hip and fashionable of their respective social spheres — or, at least, to those who wanted to be “hip.”

Far too many people to be truthful claimed only to read Playboy for the articles, but the works of respected authors and discussions of controversial social issues were tucked in and around the centerfolds. (For those too young to know what a “centerfold” is … never mind).

Rolling Stone brought counter-culture to the masses — an interesting social sleight-of-hand — and documented decades of societal change along with the authors and photographers who ushered us into a new kind of journalism populated by master storytellers and photo artistry.

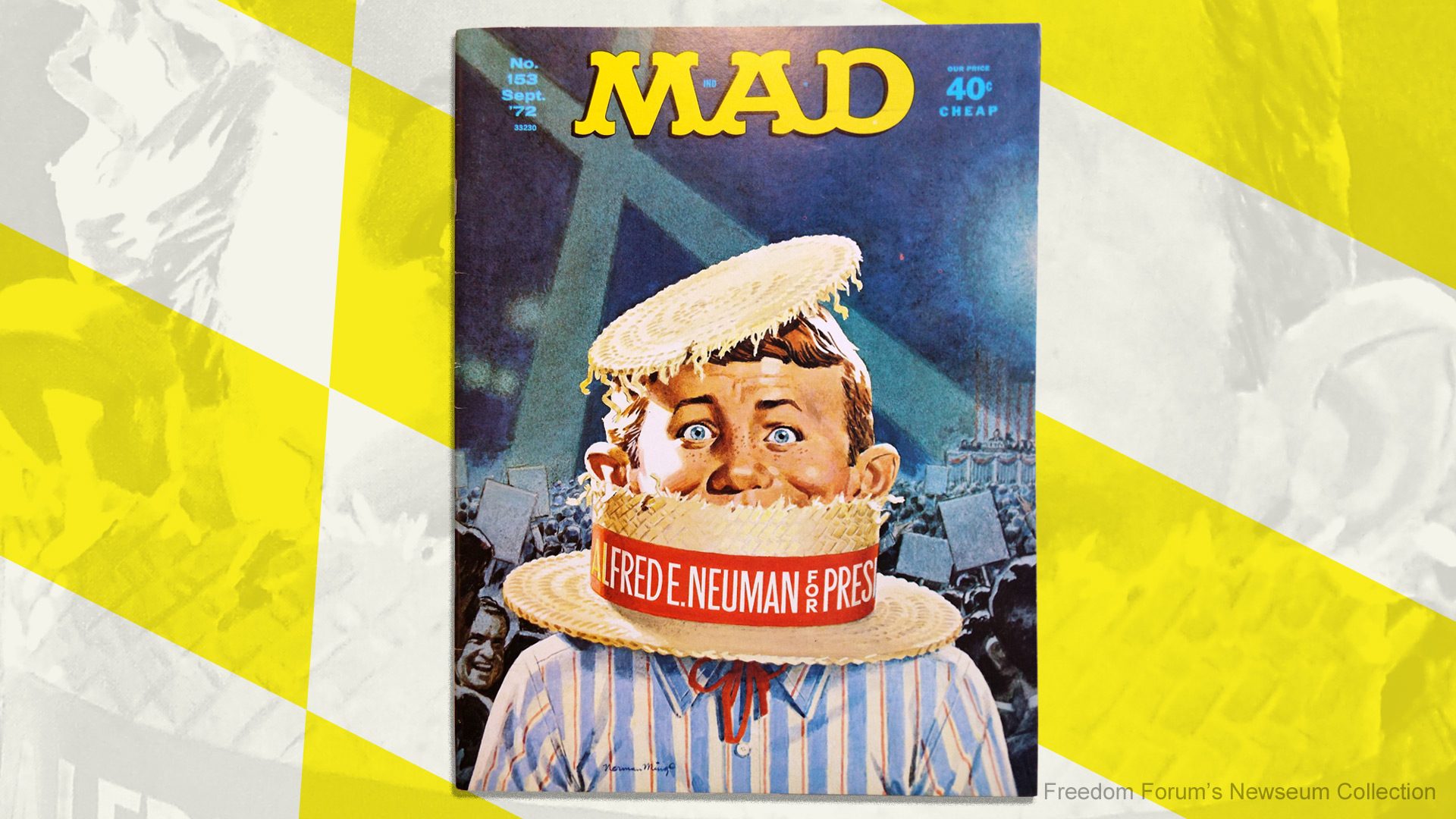

MAD, on the other hand, remained for much of its life the same as it was when launched in 1952 — a wonderfully juvenile, cleverly illustrated, delightfully snickering means of mocking adult foibles, politics and cultural institutions that were way too full of themselves.

Unabashedly egalitarian, it did not matter if its pages mocked Democrats or Republicans, beloved or despicable characters, Hollywood celebrities, literary giants or cultural icons. Linking any and all to a good joke involving flatulence worked every time.

The magazine’s apolitical satirical range may well have been captured best in an October 1968 cover in which perennially grinning MAD icon Alfred E. Neuman (catch phrase: “What, me worry?”) was shown holding a bevy of balloons, each bearing the names and faces of eight politicians from Richard Nixon to George Wallace to then-President Lyndon Johnson, in one hand — and a large hatpin in the other.

MAD and Neuman recently popped back into the nation’s headlines, but it was a mixed blessing. President Trump compared Democratic presidential hopeful, Pete Buttigieg, to the gap-toothed, youthful character and said, “Alfred E. Neuman cannot be president of the United States.” But 37-year-old Buttigieg said he didn’t know what 72-year old Trump was talking about, “I’ll be honest. I had to Google that,” he said. “I guess it’s just a generational thing. I didn’t get the reference. It’s kind of funny, I guess.”

Unlike European nations, where published satire to this day often carries a heavy intellectual tone and poses existential questions of life and death, MAD would hold up a goofy, slightly bent mirror to make fun of serious absurdities in American life. It spoofed the Cold War via a silly cartoon strip titled “Spy vs. Spy,” in which each side would attempt to foil the other, always ending in mutual death.

All the while, we eventually realized, it also was parodying the acronym for nuclear war’s likely outcome of “mutually-assured destruction” or “MAD.”

The magazine’s writers — the “usual gang of idiots each issue noted — made fun of movies, TV shows, political figures, social mores and often touched on subjects not often touched on in regular media, from drug abuse in the military to sexism in the workplace.

In that manner, it led the way for a more topical, edgy style of entertainment linked to the news, from TV’s “Rowan & Martin’s Laugh-In” in the 1960s and “Saturday Night Live” beginning in 1975 to The Onion and Comedy Central’s “The Daily Show with Trevor Noah” today.

MAD took a baser approach than some. Esquire magazine’s annual “Dubious Achievement Awards,” which began in 1962 and continue to this day, manage to convey a much more sophisticated tone in its photo-and-punch line format, even though a hallmark image was Richard Nixon, mouth agape, with the repeated line, “Why is this man laughing?”

Both magazines managed to transmit the sense to several generations of readers that pomposity deserves to be deflated, the arrogant warrant comeuppance, politicians are not always to be believed — and that it was good to be skeptical, but not so cynical you couldn’t laugh at life.

Once, MAD even helped develop legal precedent: In 1961, music publishers who represented famous songwriters and composers sued MAD for $25 million, claiming copyright infringement — the words were changed, but the parody was to be sung to the tune of the original composition. One example: To the award-winning tune, “The Last Time I Saw Paris”, MAD had rewritten it to poke fun at a baseball player who endorsed razor blades and beer on TV, in “The Last Time I Saw Maris.”

The U.S. Second Circuit Court of Appeals found for the magazine — in Berlin v. EC Publications, Inc. (219 F. Supp. 911, S.D.N.Y., 1963) — setting the precedent that has protected musical parodies since — as long as all or most of the original lyrics are changed.

Still, if we are honest, much of MAD content was just aimed at getting a good guffaw out of its fans. For example, one cartoon series showed two men mocking unseen dogs for barking at passing cars. As I recall, one said something like, “Hey, let’s see what they do with the car if they catch up with it.” Cut to the closing panel, where the other man says, “Well, now we know … so let’s find a car wash.”

I can still hear my fellow fifth-graders roaring with laughter over that one.

Gene Policinski is a senior fellow for the First Amendment at the Freedom Forum. He can be reached at [email protected].

Watch: Policing Rap Music Lyrics Challenges Free Speech

‘She Said’ and 24 More Movies About Journalism, From the Heroic to the Dark

Related Content

$30,000 Giving Challenge

Support the Freedom Forum’s First Amendment mission by Dec 31st and double your impact.