A First Amendment Framework for Effective Dialog in the Classroom

With August upon us, many Americans are preparing for their children to return to school. Educators find themselves balancing the concerns that in-person learning is too dangerous with the potential for students to behind academically in the post-COVID digital classroom.

Unlike classroom environments in the past, both teachers and students are navigating a new, virtual space that presents exciting and intimidating challenges. Chief among those challenges is creating the right setting for students to learn. It is more important than ever for teachers to create spaces that make students feel safe to express their beliefs and to encourage them to fully participate in the learning process. There are many good and best practices for creating spaces that can be adapted for use online.

We suggest beginning with a constitutional framework that teaches students how to enter effective dialogue with their peers and understand their differences without fear or derision. This civic framework can serve as a strong foundation for students, inspiring them to learn, participate and grow from a place of safety and is derived from the Williamsburg Charter’s three key principles:

- The reaffirmation of the inalienable rights guaranteed by the First Amendment;

- The reconstruction of an American public square that hinges on shared responsibility to protect those rights, even when we disagree;

- The reappraisal of how we communicate about disagreements, to begin our conversations from a place of respect rather than conflict.

Rights

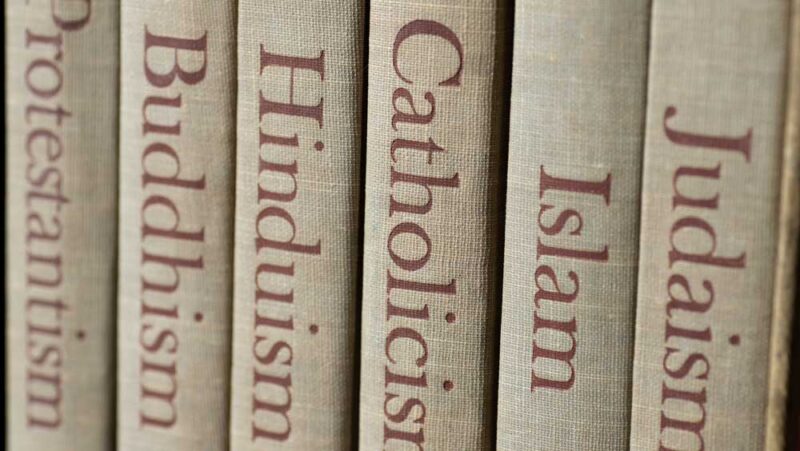

The drive to learn and understand more about our world is fundamental to human nature and that search has produced countless ideologies, beliefs, communities and ways of living. The founding fathers, particularly George Mason and James Madison, understood that in order to create a country founded on shared values rather than shared ethnicity or experiences, they must protect this inherent human drive. The First Amendment begins with, “Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof.” Often called the “religious liberty” clauses of the First Amendment, many assume that these clauses define a strict separation between state and religious institutions. While true, such an interpretation can unintentionally subordinate a more important takeaway: That all Americans have a right to believe and practice (to a certain extent) their deepest beliefs, regardless what their neighbors may think. For students, understanding that they too have been granted this right and that their teacher, like the government more broadly, consciously acts to protect that right in the classroom, can be empowering and liberating. When students know that they can bring their whole selves to the discussion, they are better able to participate and learn while feeling personally engaged.

Responsibility

As history has shown, our rights are best protected when we actively fight to ensure those rights apply to others. In the battles for civil and human rights, whether in the 1960s or 2020s, Americans have found that working together across their differences to safeguard the rights of all is a fundamental part of seeking change and creating inclusive, thriving communities. Recruiting students to participate in a mutual, reciprocal compact to protect the rights of their peers allows them to be a meaningful part of how their classroom environment is constructed, further engendering a sense of personal accountability in the learning process. Students must understand that the American experiment in democracy is not self-sustaining, but requires all participants, regardless of their disagreements, to be responsible for protecting the rights of others.

Respect

How we enter dialogue is equally important. Too often, today’s debates are publicly and privately full of ad hominem attacks and vitriol, something students are all too likely to emulate. Asking students to be active constructors of the classroom environment they would like to learn in creates a shared investment in the outcome and empowers them to feel brave and open to instruction. An effective and fun activity for students is to ask them to describe their ideal learning space: What does it sound like? What does it look like? What does it feel like? How are others behaving? If possible, have students discuss their answers as a group before collecting them and generating a series of rules or guidelines that will shape tough conversations for class periods to come.

We've seen success using this model to prepare teachers, administrators and district leaders to impart the critical skills of effective dialogue to their students in this challenging new environment.

When teachers and students model the rights and responsibilities granted by the First Amendment, not only does the classroom become a dynamic site for understanding ourselves and others, navigating difference and learning with our whole selves, but students also practice the skills and tools necessary for living in a diverse democracy — a proficiency perhaps never more important than it is today.

David Callaway is the former religious freedom specialist for the Freedom Forum.

Trey Daniel is formerly education manager of the Georgia Rights, Responsibility, Respect Project, an education initiative of the Religious Freedom Center.

Are Religious People Really Ignorant About Religion?

Related Content