Humor, Satire: Making the Political ‘Cut,’ From Our Earliest Days

The 2020 election is no laughing matter — except that it is, in the great American tradition of humor and satire that has marked virtually every election.

This time around: Jim Carey’s nascent “Joe Biden” and Alec Baldwin’s long-running “Donald Trump;” the late-nightly salvoes of Stephen Colbert and the daily — sometimes hourly — haranguing tweets from Trump himself; conservative talk radio’s sharp-edged verbal darts and the Lincoln Project’s wickedly humorous videos.

As it has since the 1970s, NBC’s “Saturday Night Live” again steps into the role of the nation’s satirist, continuing a tradition that stretches back nearly 250 years, into the colonial era with its biting print depictions of King George III and frequent effigies burned or hung from trees in public squares.

The First Amendment’s protection of free speech shelters those who poke, prod and even anger those in power — via satire and parody — and elections bring out those efforts tenfold.

Thomas Jefferson and John Adams tossed insults and satirized images of each other in competing newspapers in the 1800 presidential race. Blunt, single-sheet cartoons were hung in taverns and homes depicting Andrew Jackson as a ruthless authoritarian. One, published in 1830, showed him dressed as a king, complete with crown, trampling on the U.S. Constitution.

“Political satire has been used throughout American history as a more gentle way of commentary,” says Alison Dagnes, a Shippensburg University political science professor and author of the book “A Conservative Walks Into a Bar: The Politics of Political Humor.”

One recurring question: Why there are more liberal political satirists than conservatives, both today and in the past? Dagnes writes that “conservatism supports institutions and satire aims to take those institutions down a peg … the very nature of satire mandates challenges to the power structure.”

Two modern-day comedians exemplify those who have swum against that liberal tide: Dennis Miller, who pivoted to a conservative view after the Sept. 11 attacks, who said of his political views that he found “liberalism is like a nude beach — it sounds great until you get there.” And self-described “libertarian conservative” P.J. O’Rourke, who said the Obama administration was simply “the Carter administration in better sweaters” and supported Hillary Clinton in 2016 over Trump, saying “She’s wrong about absolutely everything, but she’s wrong within normal parameters.”

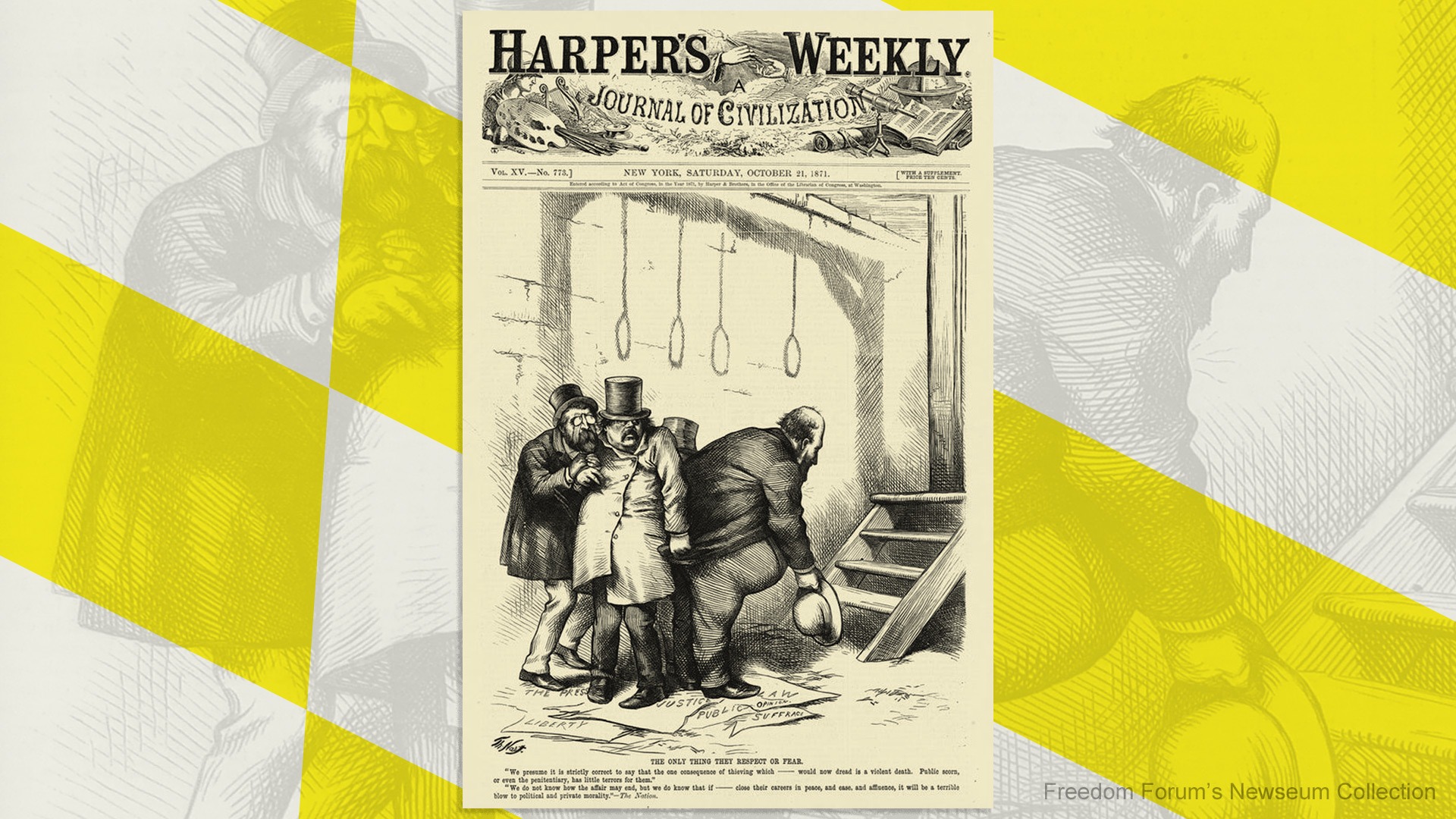

How effective can satirists be in shaping events in the real world? William “Boss” Tweed, whose crime syndicate in the 1870s stole or extorted more than $2 billion dollars (today’s value) in public funds, was the target of Harper’s Weekly cartoonist Thomas Nast. Nast drew the corpulent Tweed as a bulgingly fat character with a money bag in place of his head and historians often credit Nast as fueling the charge to bring Tweed to justice.

Another Nast cartoon of note, as seen to the left, from the Freedom Forum’s Newseum collection, “The Only Thing They Respect or Fear,” shows Tweed doffing his hat to a row of hangman nooses, as his cronies cringe in fear.

Political cartoonists are credited with helping Abraham Lincoln win reelection in 1864 and a century later, The Washington Post’s Herblock (Herbert Block) was viewed by critics and admirers as a major reason the Watergate scandal remained in public view even as the administration worked to downplay it.

Block relished his work, writing that it was “an irreverent form of expression, and one particularly suited to scoffing at the high and the mighty. If the prime role of a free press is to serve as critic of government, cartooning is often the cutting edge of that criticism.”

Social media often focuses on the “cut” in cutting edge: When Trump returned to the White House from treatment for COVID-19, satirists immediately posted their own version of his purposeful balcony appearance and maskless salute — from titling single images as “Benito Trumpolini” (after a similar pose by Italian dictator Benito Mussolini) to a Lincoln Project video, “Covita,” parodying the lyrics from Broadway showtune “Don’t Cry for Me, Argentina” as “Don’t Cry For Me, White House Staffers.”

Trump has done his own part on social media to carry satire forward in history, with memorable tweeted nicknames such as “Sleepy Joe” (Biden), “Crooked Hillary” (Clinton), “Little Marco” (Rubio) and “Lyin’ Ted” (Cruz).

Mark Twain, often called the father of modern American satire, wrote such classics as “Huckleberry Finn” and “A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur’s Court” using exaggeration and irony to make fun of closed-minded, corrupt officeholders and religious hypocrites.

A direct Twain descendant-in-humor, early radio celebrity and newspaper columnist Will Rogers used homespun language to jab politics in general. “I don’t belong to any organized political party,” he once said. “I’m a Democrat.” Another line from Rogers: “The trouble with practical jokes is that very often they get elected.”

“Saturday Night Live” (SNL) and “The Daily Show,” with comedians Jon Stewart and now Trevor Noah, have set the tone for modern political satire.

Each election cycle for more than 40 years, SNL has produced memorable political parody — from Chevy Chase’s devasting portrayals of Gerald Ford (actually an accomplished athlete) as a bumbler, to Phil Hartman’s cheeseburger-guzzling Bill Clinton, to Tina Fey’s remarkable and transformative skewering of 2008 GOP vice-presidential candidate Sarah Palin.

Stewart’s prominence in political satire from 1999 to 2015 produced a unique form of praise: Some credited him and his program as a new form of journalism. While his staff of writers and researchers included former journalists as fact-checkers to ensure accuracy, Stewart consistently said he put comedy first. Still, as my Freedom Forum colleague Patty Rhule said of Stewart and his program in a New York Times interview about the show as centerpiece of the Newseum’s 2019 “Seriously Funny” exhibit: “For a generation, he was their voice of the news.”

Stewart was the latest iteration of post-World War II comedians willing to take on social mores, censors and sometimes the courts: Mort Sahl and Lenny Bruce both mocked powerful political figures of their era — with Bruce famously being prosecuted for using so-called “blue” language that today is a common feature across cable TV comedy specials.

For two seasons in the late 1960s, brothers Tommy and Dick Smothers used satire via a prime-time CBS variety show — prompting President Lyndon B. Johnson to make an angry late-night call to network President William S. Paley. The show later was canceled over fights with network censors.

“Doonesbury” cartoons have made fun of presidents and politicians and found humor and targets across American culture since the 1970s. But writing in 2015 in The Atlantic, cartoonist Gary Trudeau reflected on whether there are lines not to be crossed in satire.

In 2015, terrorists angered at French magazine Charlie Hebdo’s criticism of Islam and reprinting of cartoons of the Prophet Muhammad that had originally appeared in the Danish newspaper Jyllands-Posten, attacked the magazine’s Paris office, killing 11 staffers and a security officer.

“Traditionally, satire has comforted the afflicted while afflicting the comfortable. Satire punches up, against authority of all kinds, the little guy against the powerful,” Trudeau wrote. “By punching downward, by attacking a powerless, disenfranchised minority with crude, vulgar drawings closer to graffiti than cartoons, Charlie wandered into the realm of hate speech.” Trudeau called the resulting violence a “bitter harvest.”

Whether they entertain or enrage, inspire or infuriate, comfort or inflame, humor and satire in a political setting often serve to bring out truths. From the subtle to the complex, satire focuses us on facts that otherwise might be lost in the daily horserace reporting that dominates modern-day election reporting.

As that 21st-century sage Homer Simpson once observed, and was quoted in a different Newseum exhibit, First Amendment freedoms of speech, petition and assembly do not exist to protect “burping” — they are there to allow us to speak to our fellow citizens about matters of public importance.

Satire and parody provide information, a release from the seriousness of much of politics and are a means to express ideas that might not find audiences in other settings.

Humor with an edge has been part of American political life as long as there was life in American politics. There’s no requirement that we be polite, respectful or even tasteful in doing it — and there’s also no barrier to getting a laugh at the same time we make a point.

Gene Policinski is a senior fellow for the First Amendment at the Freedom Forum. He can be reached at [email protected].

The Next Battle Against Government Funding in Religious Schools?

Related Content