15 Freedom of Assembly Examples You Should Know

The First Amendment protects the right to assembly, meaning the government cannot interfere with a person’s right to assemble.

Assembly includes gathering with others to organize, plan, campaign and raise awareness for causes.

Assembly can mean formally gathering, through membership in advocacy organizations with regular meetings, for example. It can also mean gathering informally, such as in spontaneous protests outside the U.S. Supreme Court after a contentious ruling.

Assembly can mean gathering privately in an activist’s home. It can also mean gathering publicly on the National Mall.

Like other First Amendment freedoms, the right to assembly is not unlimited.

The First Amendment does not protect violent protests or illegal acts within a protest, like blocking a street. Nor does it protect protest speakers who incite others to engage in immediate acts of violence, who threaten others, or who seek to provoke others into a violent response.

And public protests can be regulated for reasons unrelated to the message being conveyed. For instance, the time, place or manner of a protest can be restricted. A city could require permits to protest and could require that protests only occur during the daytime, do not occur outside a hospital, and/or not use speakers to amplify noise beyond a certain level. But the city could not deny a permit to a group protesting because of its views.

People in the U.S. have been exercising the right to assembly since before the First Amendment even existed. In this post, we explore 15 freedom of assembly examples, highlighting how this freedom has been used throughout history.

Freedom of assembly examples throughout US history

1. Constitutional Convention | May-September 1787

The first freedom of assembly example on this list took place just a few years after the United States became independent, before the Constitution existed. A group of politicians met informally at the home of Benjamin Franklin, one of the Founding Fathers. They thought the early American government wasn’t quite working. They called for a convention to revise the Articles of Confederation that loosely tied the original states together.

Fifty-five delegates met regularly at Independence Hall in Philadelphia. They also had additional meetings and informal gatherings outside the formal convention. The group worked largely in secret so that participants could feel free to disagree, change their minds and not worry about their political images.

After many compromises, they proposed the Constitution, which the states ratified and still defines the United States’ system of government today. One of the compromises was a promise to add amendments protecting fundamental rights. In 1791, those were ratified as the Bill of Rights.

2. Pullman Strike | June-July 1894

In 1894, an economic depression led the Pullman railroad car manufacturing company to cut wages. Workers organized and voted to strike. The American Railway Union decided to support the striking Pullman workers with a boycott of Pullman train cars.

Soon, U.S. mail trains were delayed. The federal government went to court, and for the first time, a federal court ordered an end to the strike. The federal government sent troops to keep the trains moving. Union president Eugene V. Debs urged the workers to protest peacefully, but riots broke out.

The strike ended, and workers who pledged not to join a union again were rehired.

The suppression of the strike was so unpopular that President Grover Cleveland created Labor Day to honor workers.

Much later, in 1945, the Supreme Court said union organizers have a First Amendment free speech and assembly right to tell people about unions.

US Cavalry escorting a meat train from the Chicago stockyards during the Pullman Strike in 1894.

3. Alabama bus boycott | 1955

In the 1950s in Montgomery, Alabama, Black bus passengers were required to sit in the back of the bus and give up their seats for white riders. Some – most famously, NAACP secretary Rosa Parks — refused to do so and were arrested and convicted of violating a segregation law.

Black bus riders decided to organize and plan a protest for change. The newly created Montgomery Improvement Association, with Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. as president, set up carpools and boycotted city buses.

As one of the first major protests of the Civil Rights Movement, the protest faced obstacles. Many protest leaders were arrested for interfering with business. The city made the carpools illegal. A judge ruled that the segregation had to end, but the city of Montgomery did not follow the order.

The city government did not give in until the Supreme Court ordered the segregation to end.

RELATED: 25 Black civil rights activists you need to know

4. Freedom Rides | May – December 1961

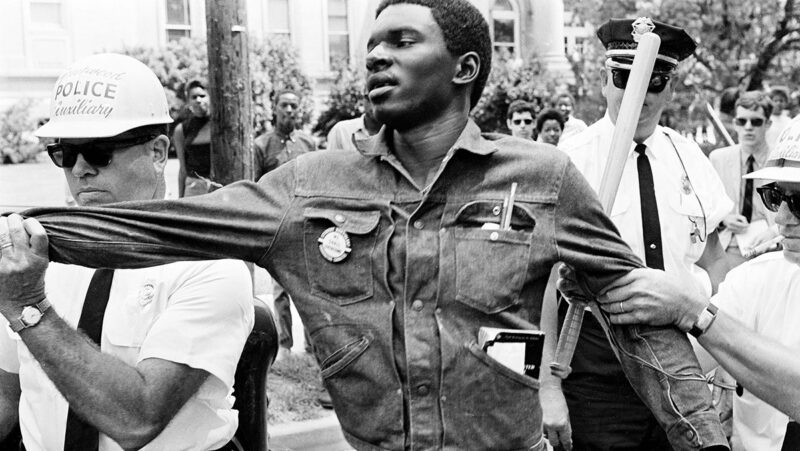

For seven months in 1961, a group of 13 civil rights activists traveled from Washington, D.C., through the South on a bus. Riders purposely violated segregation laws to test them in court after the Supreme Court ruled in 1960 that segregation was unconstitutional. Riders included the late U.S. Rep. John Lewis and Ernest "Rip" Patton.

Riders were met with violence that ended the first ride. Rides later resumed with federal protection. Many were arrested for unlawful assembly.

Eventually, the Riders were successful in advocating for an end to segregation on interstate buses and trains.

5. March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom | Aug. 28, 1963

The 1963 March on Washington is best known today for the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr.’s “I Have a Dream” speech, making this one of the most well-known freedom of assembly examples on this list.

A defining moment of the Civil Rights Movement, the Associated Press estimated more than 200,000 demonstrators gathered at the Lincoln Memorial to advocate for social and economic equality.

The carefully planned, peaceful rally organized by a coalition of civil rights groups featured speeches and songs. Many members of Congress attended, and organizers also met with government officials to advocate for the passage of a civil rights bill.

Attendees signed a pledge to keep advocating for jobs and freedom.

Crowds are shown in front of the Washington Monument during the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom.

6. LGBTQ+ job rights pickets in Washington | April 1965

After Frank Kameny was fired from his civilian Army job for being gay, the Supreme Court declined to hear his petition. Despite the risks associated with being publicly identified as gay, Kameny organized an LGBTQ+ rights picket of 10 anonymous protestors at the White House on April 17, 1965. The group later held more protests at other locations around Washington, D.C., always wearing sharp business attire and holding signs with bold language.

The protests eventually generated national news coverage, and organizers founded a gay rights society chapter in D.C. to advocate for equal rights.

7. Chicago Democratic National Convention | Aug. 26-29, 1968

1968 was a turbulent year with many freedom of assembly examples. Vietnam War protests and the assassinations of the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. and presumed Democratic presidential nominee Robert F. Kennedy had the country on edge.

At the Democratic National Convention in Chicago, a divided party needed to pick a nominee.

Amid the tense atmosphere, Mayor Richard Daley refused some groups’ requests to protest, calling the police and the National Guard to ensure security.

Inside the convention, the news media protested Daley’s security restrictions and much of the proceedings aired on live TV. Disagreements over the party platform increased the tension, and the party later revised some of its rules for nominating candidates.

Meanwhile, anti-war demonstrations in nearby Lincoln Park and elsewhere around the city grew, some turning violent and many being quashed by police. One march down Michigan Avenue to the hotel where many convention delegates were staying was teargassed by police. The gas wafted into the hotel, all broadcast live on television.

Some protesters were later tried for conspiracy and intent to incite a riot, yielding mixed verdicts that were later reversed as reports concluded that the police response was too heavy-handed.

8. March for Life | January 1973 – Ongoing

Each year since the Supreme Court's decision on Roe v. Wade protected the right to abortion, the March for Life in Washington, D.C., has protested abortion access. The march has continued since that case was overturned in 2022.

Founded by Catholic lawyer Nellie Gray, the march includes people of many religious and nonreligious backgrounds.

Behind the scenes of the annual march is yearlong organization in support of candidates and policies to oppose abortion access.

March for Life demonstration in front of the White House in January 1982.

9. AIDS protests | 1980s

Another prominent freedom of assembly example took place in the 1980s as AIDS began to spread and many found the government response inadequate.

The AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power, or ACT UP, was one group that assembled to advocate for and create change.

The group demonstrated in New York City at City Hall and on Wall Street. Protests that blocked traffic led to more than 100 arrests. The group also staged a “die in” at the Food and Drug Administration in Maryland, leading the FDA to agree to meet with representatives to discuss possible drug treatments. The group also held “kiss-ins” to protest discrimination against LGBTQ+ people who were particularly affected by HIV/AIDS, including at St. Patrick’s Cathedral and Christopher Street in New York City and hospitals with discriminatory practices.

ACT UP also provided direct assistance, organizing social services for people with HIV/AIDS.

10. California Chicano hunger strikes | 1993-1994

In the mid-1990s, students at several universities in California, including the University of California, Los Angeles, the University of California, Santa Barbara, and Stanford University protested policies that immigrants from Central and South America found harmful and sought support for Chicano studies programs.

Students staged hunger strikes and sit-ins. Amid the demonstrations, some students were arrested. But the protests did impact the schools, including leading to the establishment of the UCLA César E. Chávez Department of Chicana/o and Central American Studies.

11. Anti-war on terror protests | 2001-2003

After the Sept. 11, 2001, terror attacks, the nation began a multifront war or terrorism in Afghanistan and Iraq.

Freedom of assembly examples began when anti-war protests were held as early as Sept. 29, with a rally and march in Washington, D.C. While some anti-war groups were associated with controversial views, many attracted widespread support.

On Feb. 15, 2003, the protests in cities around the world may have been the biggest anti-war protests since the Vietnam War era. A month later, the U.S. invaded Iraq. However, the protests showed how unpopular the military escalation was and may have influenced policy decisions around the decades-long occupation.

Anti-war protesters gather outside the United Nations Headquarters on Feb 15, 2003 in New York to protest a possible U.S.- led attack on Iraq.

12. Black Lives Matter | 2013-Present

The Black Lives Matter movement began with a hashtag. In reaction to the deaths of Black men at the hands of law enforcement, its use grew. The slogan has become a grassroots movement that includes a decentralized organization of local chapters.

It caught fire nationwide following the May 2020 killing of George Floyd by a Minneapolis police officer, which led to protests around the country.

Activists associated with the movement have advocated for police reform through protest, direct action and petition.

RELATED: 20 of the most famous protests in U.S. history

13. March for Our Lives | March 24, 2018

On Feb. 14, 2018, 17 people were killed and 17 more injured in a shooting at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School in Parkland, Florida. Four days later, students at the school announced that they planned a nationwide protest, including a march on Washington.

On March 24, the student-organized march drew crowds to Pennsylvania Avenue in Washington, D.C. While many of the organizers were not yet of voting age, they exercised their freedoms of speech, assembly and petition in calling for change.

The student-led organization behind the march continues to assemble and petition for “a future free of gun violence.”

14. COVID-19 restrictions protests | Spring 2020

Many state and local governments imposed stay-at-home orders due to COVID-19’s rapid spread in the spring of 2020.

Organizers, citing civil liberties and economic concerns, planned protests in many cities. Demonstrators gathered at the Michigan state capitol, and the BBC reported 2,500 protesters in Olympia, Washington.

Facebook said it would remove event information for protests that violated state government orders.

Restrictions on gathering led to lawsuits as well as protests.

Two protesters who were arrested at a protest in a New York City park sued over COVID restrictions on nonessential gatherings, but their First Amendment lawsuit was dismissed.

The Wisconsin Supreme Court upheld restrictions on gathering.

The U.S. Supreme Court first rejected, then later supported, a religious freedom claim to overturn limits on gathering for religious services.

Protests lasted through 2022, including a January 2022 march in Washington, D.C., in protest of vaccine requirements.

People march alongside the Lincoln Memorial Reflecting Pool before an anti-vaccine rally in January 2022.

15. Israel-Hamas war protests | October 2023 into 2024

On Oct. 8, 2023, protesters gathered in Times Square in New York City. The day before, Hamas, a Palestinian militant group that has controlled the Gaza Strip since 2007, had attacked Israel from Gaza.

Demonstrations across the world including in the U.S. grew in support of Palestinian people affected by the counterattacks. So did demonstrations for Israel and the safe return of Israeli hostages held by Hamas.

On Nov. 4, protesters in Washington, D.C., held a march for Palestine. On Nov. 14, the city was the site of a march for Israel.

Protests in front of the White House and inside government buildings led to hundreds of arrests.

Protests particularly escalated on college campuses across the country, including sit-ins and encampments on university quads, generating controversy over the limits on freedom of speech and assembly.

RELATED: Protesting on college campuses: FAQs answered

Examples of current challenges to assembly

As long as these freedom of assembly examples have existed, there have been questions about the limits of the freedom to assemble. Many of those questions remain today.

Are protest organizers liable for violence? In April 2024, the Supreme Court declined to stop a lawsuit by a police officer injured during a protest against DeRay Mckesson, the organizer of the protest.

Can participation in public meetings be limited to keep order? Contentious school board and city council meetings have led to some limits on public participation. But there have also been successful lawsuits in which courts have said officials’ actions and rules to keep meetings from getting heated went too far in limiting participation.

How much can cities and states limit protest in the name of safety and order? Protests are inherently disruptive, but how much disruption is too much?

When do campus protests go too far? How can public universities both prevent harassment of opposing students and protect First Amendment freedoms?

Questions like these have been asked since before the First Amendment even existed and continue to be shaped by activists pushing the boundaries of free assembly and courts interpreting this key freedom.

The Right to Be Forgotten: Everything to Know About Erasing Digital Footprints

Related Content